Photographers want one simple thing. They want to make great images. I think most people who set out to achieve this goal believe there are two essential steps to get there. Step one is to develop the requisite set of tools & techniques. They get a camera with the features & functions they need and they learn how to use it, along with all the typical accoutrements, including flashes and tripods along with editing software (Lightroom, Photoshop, etc. etc.).

Step two is to find interesting things to shoot. It is this quest that drives many photographers to distraction and beyond. It is the wellspring of global adventuring to the four corners of god-knows-where in pursuit of the ultimate landscape, the rarest wildlife, and the most exotic cultures. All of this sits on the foundation of a simple, strong, and essentially competitive impulse: if I shoot the coolest thing, I will have the coolest image. I just have to find the coolest thing before anybody else does.

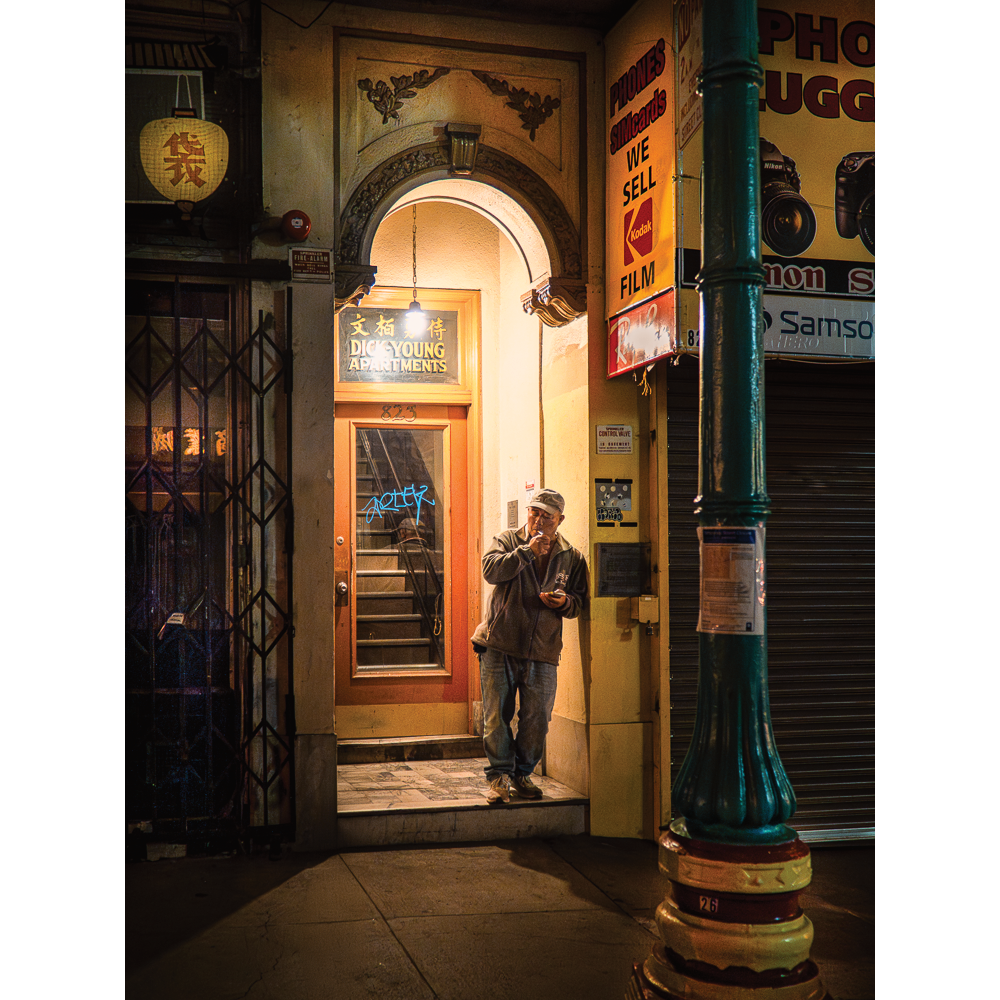

A few years ago, I was with a crew of friends and fellow shooters doing street photography in Chinatown. We rarely did street photography, because we found it a bit intimidating and stressful. But there we were, when suddenly we heard the sound of firecrackers and music. We all immediately had the same thought: whatever that is, it might make for a cool photo!! Without a word to each other, we were off in pursuit of the noises. We fast-walked and ran until we caught up with a small group doing a traditional Chinese New Year ritual. There was a beautiful dragon costume with wonderful dancers inside, accompanied by costumed drummers and the lighting of firecrackers to ward off evil spirits. How lucky can you get? We all thought we had died and gone to street photography heaven!

I’ll skip to the punchline here – the photos were awful. They were “technically” fine. They were in focus, well exposed, well composed, and very boring! As I stared at my computer monitor and wondered what went wrong, it began to dawn on me: these were not above-average images from Chinatown on a day that I got lucky. They were well below-average images of something I’ve seen a million times, in a million different places. They were not new, novel, or surprising in any way. The image of a dragon or a lion dance for Chinese New Year is one of the most photographed subjects in the world, and the best of those images are done by elite photographers in much more dramatic settings and finished by world-class photo retouchers. My photos had nothing new to offer.

So what was I doing there? In retrospect, I was missing whatever visually arresting things that were certainly happening around me, while I was busy chasing a cliche photo. Whatever Chinatown placed in my visual field that was unique and special to that particular time & place, I was never going to notice it.

Since that day, I have often thought about the difference between taking and making photographs. As I look back, it occurs to me that this distinction goes to the heart of what it means to pursue photography as an art form. In marketing, there is a phenomenon known as “borrowed interest”. A common strategy in this vein is to take something intrinsically uninteresting (like laundry detergent) and associate it with something that captures interest, like a hit movie or a #1 song. You didn’t make the movie or write the song. But that’s the point. If you capture some of the spotlight, you win. Much of commercial photography operates in this way. When you’re getting paid, the subject matter is usually what counts the most. If the NY Times sends a photographer to cover the Oscars, that shooter better come back with pictures of movie stars, or they won’t get the gig again next year. A bad picture of Tom Cruise is better than a drop-dead gorgeous photo of somebody you’ve never heard of.

But if you approach photography as an art form, the notion of borrowing interest from your subject is something worth pondering. How much of what you see in a photograph comes from the photographer? If I experience photography as a form of expression, then its important for me to ask how much of myself goes into the work I create and publish. At the heart of this is the idea of being original. What do you create that expresses your unique vision? What sets you apart? It is the selfish but necessary question all artists need to answer.

The more I shoot, the more interested I am in producing original work. When I reflect on my work, I want to see something of myself. And I want others to see that too. This desire is at the root of my passion for street photography, because it is a genre that demands originality. That may be why I found it intimidating at first, but it is certainly the reason why its my favorite genre now.

Since that unsatisfying day long ago, I have spent many more hours walking the streets & alleyways of Chinatown (among many other places). There are a million photos to be captured – endless details and subtleties that are to be found nowhere else but precisely where you stand, and in that very moment. You probably won’t encounter movie stars, rare wildlife, or even great works of architecture. But you can find something even better – something utterly distinctive, something that reflects your unique voice. You can find it, that is, if you are prepared to notice it.

And the first rule is: don’t go chasing dragons.

Follow my street photography on Instagram: @patggarvey